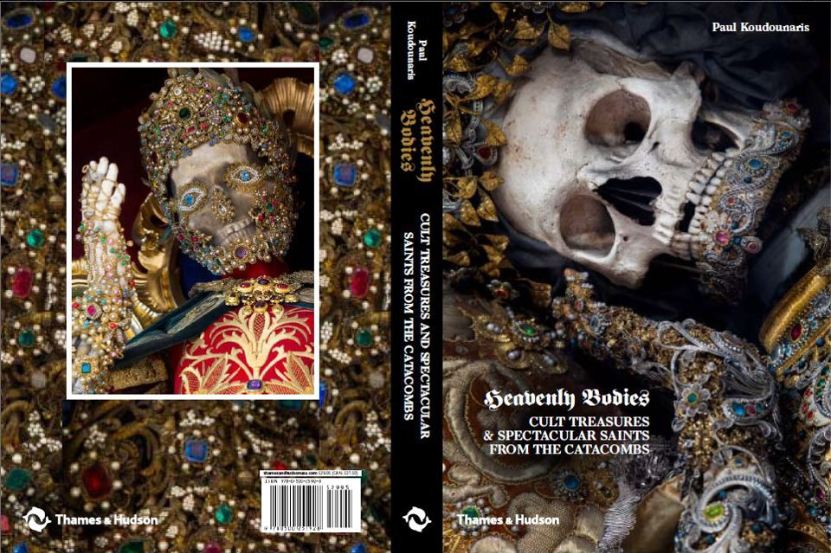

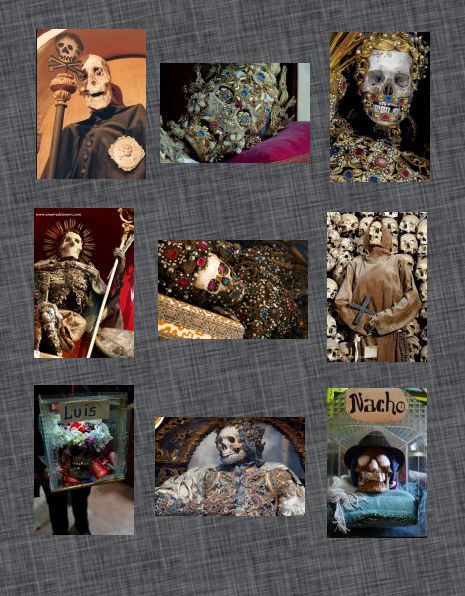

by Tracy Vanity (All photos courtesy of Paul Koudounaris)

3 more days until Halloween!

Paul Koudounaris is paranormal catnip. Unexplained and weird phenomena gravitate towards him like death moths to a preternatural flame. He specializes in finding the most unique shrines to the dead which also sometimes end up finding him.

He has extensive knowledge of ossuaries, sex ghosts, charnel houses, weird history, demonic cats, death rituals, funeral rites, and of course, skeletal bling, among many other things. Between travelling to exotic locations, taking stunning pictures of the dead, he also gives lectures on the aforementioned subjects.

Paul was kind enough to answer a few questions about his unique line of work, paranormal experiences, as well as give some tips on how to buy a human skull!

How much is a human skull and how does one obtain one? I know it’s easier to get here in Thailand but you said the one in Chatuchak was insanely expensive. How many skulls do you currently own?

The one I wanted in Bangkok was insanely expensive, but that’s because it’s a kapala, so it’s sacred and from the Himalayas. More mundane skulls should be easier to find. Human skulls in general are quite expensive now and harder to get. Dealers in the USA used to get them cheap from places like Rajasthan or China, but those channels to my knowledge have been largely suspended. The cheapest place I know of to get human skulls is Bolivia.

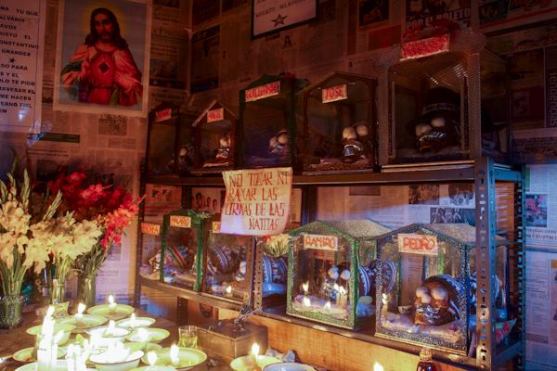

In the cemetery general in La Paz, grave space is only leased, so it’s pretty much inevitable that at some point your distant relatives will stop paying and you’ll be evicted. At that point, the bones are supposed to be broken down and dumped in a mass grave, but the skulls are typically taken by the gravediggers and sold on the side. Cheap. One lady told me she had purchased three several years back for the equivalent of 12 US dollars.

I myself only own one human skull. I used to have several others. I’m not so much into human anatomy. Animal skulls are better looking and more dramatic, they have horns and other fun things. Human osteology is in comparison a bit boring.

Is there a blinged out skeleton or skull you’d like to have in your possession if money or legalities were not a factor?

Well sure, there are several. In fact, I was so obsessed with the jeweled skeletons that at one point, when I got home from photographing them in Germany, I decided to make my own–I took a dog skeleton that I had lying around, went down to the garment district and bought a bucket full of high quality rhinestones and covered it over. I also got a crown and scepter for it, and it sits in my living room in an antique crib.

For one brief moment I thought I might be able to get one of the real ones–I was visiting a church in Switzerland that had it in storage, and they definitely didn’t want it, and one of the church maintenance guys suggested maybe they should just give it to me to get rid of it. I told them I would definitely take it and make whatever arrangements were necessary, but the local bishop soon got involved and nixed it since, even though it was unwanted, it was nevertheless a sacred item that had been entrusted into the care of the parish.

Would you like to become a jeweled skeleton after you die?

Personally I have neither desire nor aversion to being a jeweled skeleton. I don’t really care what becomes of my remains after I die. People often seem to think that because I study and photograph all these fancy skeletons that I must want to be one–well, I love them and I am glad people once made them, but my personal sense of what is important in post-mortem care doesn’t really involve that. They were part of a spiritual system at one time, so my if I had to make a verdict it would be that if one only wants to creates such things for aesthetic rather than spiritual reasons, probably best to not since lacking the spirit they I suspect be innately inferior.

Have you ever been cursed by a skeleton you’ve taken a picture of or felt like they’ve become upset for you being there?

Cursed–well not cursed, but there was one particularly notable incident. The first time I went down to Bolivia to document the Fiesta de las Ñatitas, I visited a private home of a woman who had several miracle working skulls. I interviewed her and asked if I could take photos, which she said was fine.

What kind of miracles? Whose skulls are they?

They come from the cemetery or are donated, no one knows whose skulls they are. But the identity of the living person is irrelevant. In Aymara belief, a person’s soul is made up of different aspects that all have different identities, and one of those identities will contact the owner after death, so it’s not really the person who was living, since that person was a composite.

Not to get too sidetracked into the technical aspects, but I took all the photos on film–it was nearly pitch black, and film doesn’t care how long an exposure you use, whereas if you really want to burn out the sensor on an expensive digital camera, just sit around doing a bunch of 30 second exposures, plus the pictures will look terrible in addition.

So I did these photos on both 35mm and medium format film. The latter I had developed in La Paz, the former I brought back with me to develop here. That film that was developed in La Paz was a real treasure, because it was something no outsider had seen before, and being medium format it would print huge and beautiful. I carried it in its own box on my lap on the plane back–like I said, it was a treasure. So I got home, went to bed, and I heard a voice saying “Where’s Ana?” I jumped out of bed, but there was no one there. I figured I must be delirious after a very long trip. So I went back to bed, but there was a loud thump in the center of the floor.

Again I turned on the lights–nothing. Like I said, I figured I must be delirious. I went to sleep, woke up in the morning . . . and the box containing the film was gone. It had vanished from my living room, just disappeared. I searched everywhere, called the airline and the airport, but at the same time I knew for a fact that it had come home with me and I placed it on the floor in the middle of the room . . . and that’s when things all came together. Wait, in the center of the room, that was exactly where I had heard that loud thump. And the name Ana–that was the name of the woman whose house I had taken the photos in. Weird. Kind of creepy. And the film was gone.

So I still had the roll of 35mm film, and I took it to a lab to be developed, I told them to do it asap. The guy calls me back a couple hours later and told me there had been a “problem”–the film had started to burn. What???? He said he had no explanation. I went down there and he showed it to me, this burned, charred film strip, melted throughout except for two images at the very start, which is all I had left and used them for a magazine article I wrote.

Well, the next year when I was in Bolivia I went back to Ana’s house, and told her this story. She said it was because I hadn’t gotten permission from the skulls to take the photos, so they had decided to essentially vacate, except apparently for the one in the first two frames who was apparently OK with it despite my lapse. I told her, but wait, I *did* ask permission, I asked you if it was OK, I wouldn’t have taken the photos without your permission. She replied, yes, I had asked *her* permission, but I had neglected to ask the permission of the individual skulls as well, which was insulting to them. She advised me to take more photos but ask their permission first. So I did exactly that–and every single one came out perfectly.

Paul K’s latest book, Heavenly Bodies is out now.

His next book, Memento Mori, will be released in the Spring. He is also working on a book about pet cemeteries.

You can view more of Paul K’s exquisite photography at Empire De La Mort and his Facebook page.

This post may contain affiliate links. Further details, including how this supports the bizarro community, may be found on our disclosure page.